Illustration - Winter 2017 - Issue 54

If ever you needed proof of the long and finne tradition of illustrating books, this issue demonstrates it with classics to spare. What’s more, it reminds us of the variety of skills and talents that different artists have brought to their illustration projects. As far back as the Middle Ages, artists were, literally, illuminating texts on everything from hunting to history, as well as gorgeous religious manuscripts, with endlessly creative patterns, abstract designs, paintings and strange, fantastical creatures (page 22). These books were, and are today, treasures, as much for their aesthetic beauty as for the knowledge they imparted – and have survived for that very reason.

Move forward a few hundred years and the long-lost sketchbook of wood-engraver Thomas Bewick demonstrates a similar mix of craftsmanship and creativity with a distinctly English slant (page 44). Bewick recorded what he saw around him in the British countryside. Half a century later, John Everett Millais drew on similar sources when he composed a striking scene around a wintry church bell tower and a lonely owl laden with symbolism for Edward Moxon’s volume of Tennyson, Poems(page 26). He and the other Pre-Raphaelite artists involved in this famous edition consciously referred back to their historical predecessors, yet ended up creating something that exemplified a new trend in mid-19th-century book art.

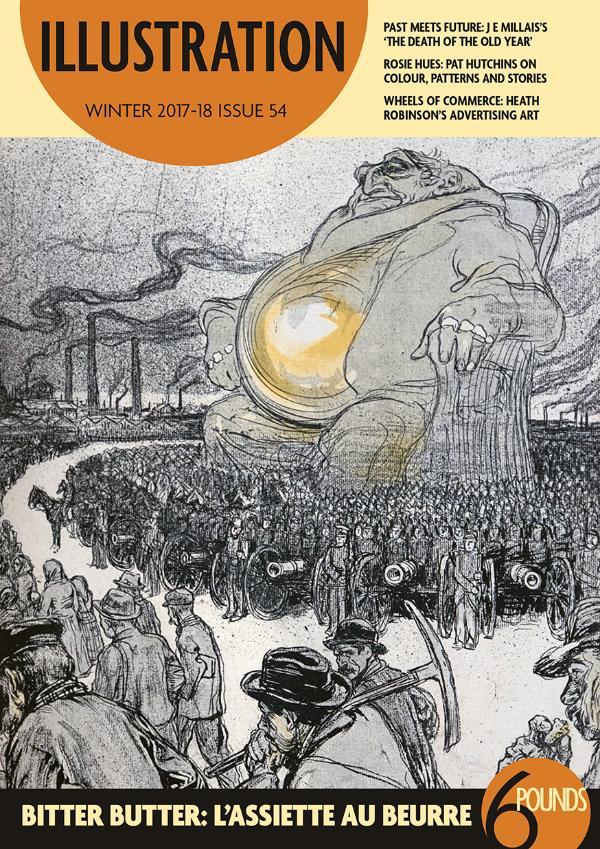

Then on to the 20th century and who better to represent the Edwardian idyll than Ernest Shepard’s Winnie-the-Pooh cavorting around Ashdown Forest (page 18). But dark clouds caused by industrialisation and war were gathering. Humour helped demonstrate the benfits of one, while casting a cold satirical light on the other – William Heath Robinson’s fantastic machinery made Britain’s factories more cosy (page 30), while over in Paris artists at L’Assiette au Beurrewere highlighting the human cost of mass production and slaughter (page 8). The future was brighter, however, by the 1960s, when Pat Hutchins returned vibrant colour and intricate patterns to children’s books that mass production ensured could be sold worldwide (page 36) – the methods were modern, yet her decorative flourishes would have been instantly recognisable to the book artists of the Middle Ages.