Illustration - Winter 2014 - Issue 42

It is rare that illustration hits the news and few illustrators make headlines until they become “national treasures” or achieve fame in another sphere, such as animation. This makes the attack on French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, which left 12 people dead, including cartoonists, all the more tragic. The irony that so many more people have seen the images that caused offence now, after the murders of their originators, than ever saw them when they were alive seems particularly poignant. Outrage (no matter whether it’s regarded as justified or whether the response to it is proportionate or legal) is the flip side of fame. Satire is, after all, published to be seen and its message understood. Upsetting people may be a measure of success – better to be reviled than to be ignored. Illustrators and cartoonists have responded to the murders with defiance and British cartoonists are now planning a book, Draw the Line Here, to raise money for their murdered colleagues’ families, but the attack may have also served to remind people about the power of images, whether they are used to shock, sell, persuade or ridicule. Society needs to remember that satire – and the arguments about the limits of free expression – are an age-old tradition and need to be discussed afresh by each generation.

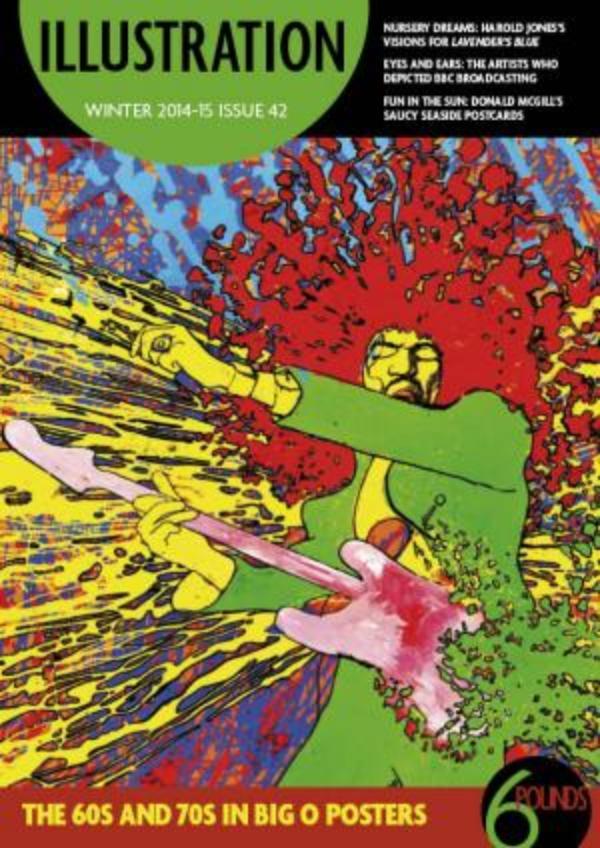

In this issue we look at the bawdy postcards of Donald McGill, who was prosecuted for profanity, despite his protests that his images were no more shocking than the music hall acts of stars such as Marie Lloyd. We consider the influential posters of the Big O Poster company that celebrated popular culture and called for changes such as the legalisation of cannabis and we rediscover the satirical illustrations of Victorian artist Ernest Griset, who depicted people as animals and made sly points that occasionally led to sharp criticism. We need illustrators who are prepared to cause offence – but they need us to agree to roll with their punches