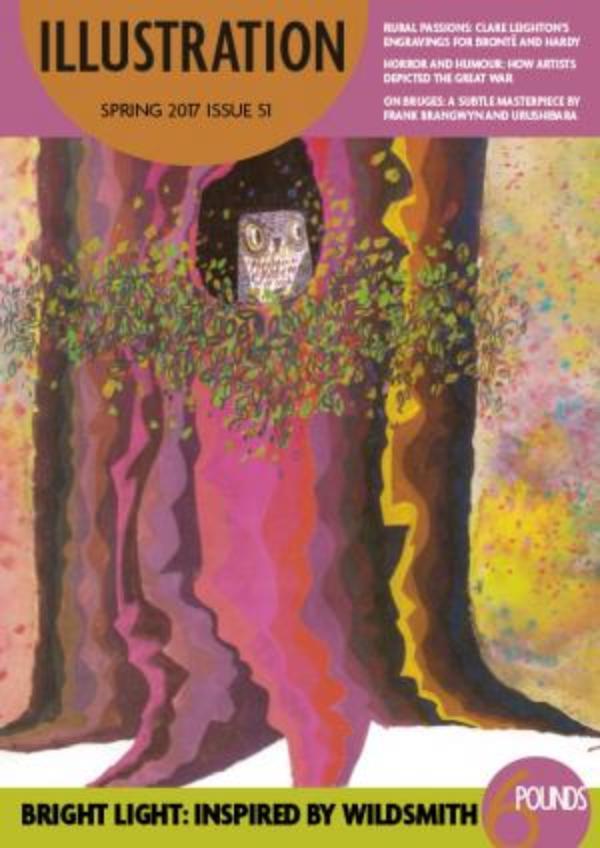

Illustration - Spring 2017 - Issue 51

One of the enduring mysteries about illustration – and art, generally – is how a few strokes of a brush, or lines scratched in a wooden block, can communicate not just a story, but an emotion or an abstract thought. The ability of art to convey and evoke emotion is well known, but in the case of illustration there are added complications. The artist has to convey their own feelings. The illustrator, however, often has to reflect those of the text or the client as well as putting something of themselves into their work. When this works well, it undoubtedly enhances the power of the text or the message of the client, but defining how this affinity works is extremely difficult.

Clare Leighton’s dramatic and powerful wood-engravings, for example, were a perfect match for the tempestuous emotions of the characters in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Thomas Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree and The Return of the Native. The simple black and white lines not only set the people in their landscapes, they also underscore the wild and often dark passions that dominate the stories. Similarly, war artists naturally used the emotional powers of their work to convey the darkest, most chaotic moments of battle as well as the most cynical and bitter feelings of loss and betrayal. They were commissioned to tell a story and boost patriotism, but their work often does far more than propaganda, commenting on the futility and utter desolation of war in a way that perhaps their employers did not quite intend. And quieter, more reflective works, such as Bruges, the portfolio of poems by Laurence Binyon, illustrated by Frank Brangwyn and Yoshijiro Urushibara, do more than merely celebrate the beauty of physical buildings, bridges and canals – they conjure up the artists’ emotional response to streets and landscapes in subtle gradations of colour and the play of light on water. Humans seem to have a natural ability to connect art to feelings. This is why illustrations can add so much more than decoration to the printed page – and why illustrated books etch themselves into the psyche of readers from their earliest days. A picture and a text together can be far greater than the sum of their parts.