Illustration - Autumn 2014 - Issue 41

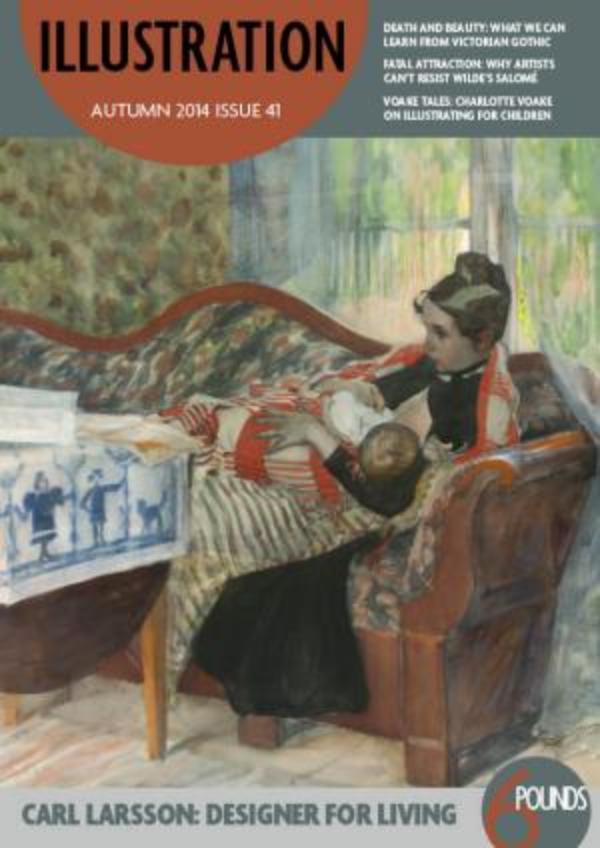

llustration, more perhaps than fine art, often tells us much about the times the illustrator lived in – even when their work depicts historical periods. Sometimes it reveals underlying anxieties and fears, as we see when we examine Victorian Gothic illustration. Gothic artists focused on historical and mythical themes such as medieval epics and Arthurian legend, but their constant depictions of, for example, a heroic, hierarchical past and powerful dangerous women, clearly express their concerns about industrialisation and social change in Victorian England. However, creating a present from an idealised past can also be comforting and reassuring, as we learn from the work of Swedish artist Carl Larsson. He wanted to be known for large historical works, but became famous for depicting an idyllic rural home he decorated in a “traditional” style based on a reinvented past. It came to epitomise Swedish interior design – and foreshadows much 20th-century Scandinavian modernism.

Some stories are particularly adaptable and manage to speak to new generations in multiple forms. Oscar Wilde’s reworking of the biblical story of Salomé has excited the imaginations of illustrators for more than 100 years. Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations added to the play’s notoriety, demonstrating the power of images to equal or exceed that of the words they accompany. These illustrations again show how images can enhance the atmosphere of a story and charge it with elements that may or may not be present in the text. In a very different style, Mary Ellen Edwards illustrated books that were set firmly in her present day, yet brought to them her own sympathies and perceptions, particularly of the situation of other Victorian women. Her fame has not endured as Beardsley’s has, yet her illustrations also tell us much about society and its concerns in the 1860s in much the same way as her Gothic and decadent successors.